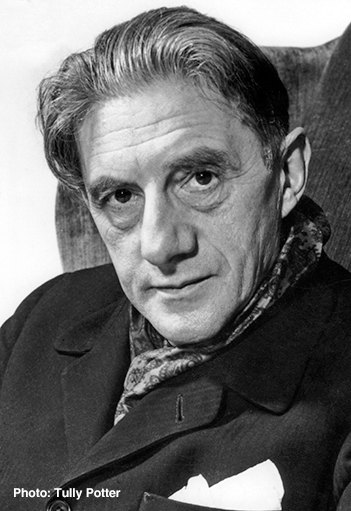

John Barbirolli

Both John Barbirolli’s father and his grandfather were Italian violinists of note. As members of the orchestra of La Scala, Milan, they had both played in the first performance of Verdi’s Otello (1887), as had Toscanini. Barbirolli’s mother was a native of the southwest region of France. He was born in London and not surprisingly was taught to play music as a very young child. Initially he learnt the violin but at the age of seven he switched to the cello. Three years later he entered Trinity College of Music, transferring after two years to the Royal Academy of Music. His first recordings were made for the Edison Bell Company in 1911, with his sister accompanying him on the piano. He started to play in Sir Henry Wood’s Queen’s Hall Orchestra during 1916, and made his recital debut at the Aeolian Hall the following year. Between 1917 and 1919 he served in the British army, where he had the opportunity to conduct a voluntary orchestra.

On returning to civilian musical life Barbirolli played with many different musical groups, from the London Symphony Orchestra and Sir Thomas Beecham’s Covent Garden Orchestra to cinema and dance bands. He gave the second performance of Elgar’s Cello Concerto in 1921. Three years later he became a member of the Music Society (later known as the International) and Kutcher String Quartets, both of whom in 1925 and 1926 recorded for the National Gramophonic Society, an early record club run by Sir Compton Mackenzie’s magazine The Gramophone. In 1924 Barbirolli also fulfilled his early ambition to conduct by forming his own chamber orchestra. In 1926 Frederic Austin, the director of the British National Opera Company, invited him to conduct the company on tour, and he made his operatic debut directing Gounod’s Romeo et Juliette at Newcastle-upon-Tyne, as well as performances of Aida and Madama Butterfly. He was to conduct the BNOC and Covent Garden Opera Company frequently over the next six years. Also in 1926 Barbirolli deputised at short notice for Beecham, conducting the London Symphony Orchestra in a highly-praised performance of Elgar’s Symphony No. 2. It was this performance which brought him to the attention of Fred Gaisberg, of HMV.

In 1927 Barbirolli started to conduct orchestral music for recordings, firstly with the National Gramophonic Society and soon after for the Edison Bell label. In 1928 he commenced his long association with the HMV label, recording a wide range of the shorter pieces that were the staple of the 78rpm record catalogue. He was particularly successful as an accompanist, recording with international instrumentalists of the calibre of Kreisler, Elman, Heifetz, Rubinstein and Backhaus, as well as many singers. In 1933 he took up the post of conductor of the Scottish Orchestra in Glasgow, where he had the opportunity to conduct many major orchestral works for the first time. In addition he conducted the Northern Philharmonic Orchestra, based in Leeds, and appeared as a guest with the newly formed London Philharmonic and BBC Symphony Orchestras as well as with the London Symphony Orchestra.

Mainly as a result of the recommendations of some of the soloists with whom he had recorded, he was offered in 1936 the opportunity to conduct ten concerts over six weeks with the New York Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra, which had just parted company with Toscanini. So successful were these that Barbirolli was offered the permanent conductorship of the orchestra for a period of three years, starting from the 1937–1938 season. During this time he earned the affection of the players, and audiences initially grew; in addition he made numerous recordings with the orchestra. However Barbirolli’s work in New York was increasingly belittled by critics enamoured of Toscanini, who continued to maintain a presence in the city with the NBC Symphony Orchestra, an ensemble which had been especially created for the Italian maestro. Barbirolli’s contract was extended for a further two years to 1942, but he was offered only a handful of concerts for the following season, 1942–1943.

In 1942 he had made a hazardous wartime journey to England by sea to conduct the London orchestras, and thus when the invitation came to him to re-form Manchester’s Halle Orchestra in 1943 the time was ripe. Barbirolli immediately accepted and in only one month, through intensive auditioning, he completely re-created the orchestra with which he was to be indissolubly associated for the rest of his life. Initially (between 1943 and 1958) he was the Halle’s permanent conductor, directing it in an exhausting annual schedule of concerts both in Manchester and throughout the British Isles, as well as on tours abroad. Knighted in 1949, in 1958 he reduced his commitment to the orchestra to approximately seventy concerts each year and took the title of conductor-in-chief.

Barbirolli now began to establish a significant international career. He became an annual and respected guest conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, with whom he recorded at the orchestra’s request. Arguably the Berlin orchestra’s mastery of Mahler stems from its work during this period with Barbirolli, rather than from Herbert von Karajan. In 1961 Barbirolli was appointed chief conductor of the Houston Symphony Orchestra in succession to Leopold Stokowski, and stayed with that orchestra until 1967; in addition he toured abroad extensively with the Philharmonia and BBC Symphony Orchestras as well as with the Halle. In 1968 he became conductor laureate of the Halle, but his unremitting schedule of concerts and recordings was by now taking its toll. Barbirolli’s last public concert was given with the Halle Orchestra at the King’s Lynn Festival on 25 July 1970. Four days later he collapsed and died, while rehearsing the Philharmonia Orchestra for a tour of Japan.

Throughout the post-war era and right up to his death Barbirolli was active in the recording studio. He recorded with two main companies: EMI, conducting both the Halle and other orchestras; and during the late 1950s with Pye, again recording extensively with the Halle. Pye produced his first stereophonic recordings. Barbirolli’s discography was very large indeed. Among its highlights are a superlative Madama Butterfly, recorded in Rome with the forces of the Rome Opera; a passionate The Dream of Gerontius; deeply-felt interpretations of the Symphonies Nos 5 and 9 of Mahler (the latter with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra), and of the Symphony No. 2 of Elgar, all on the EMI label. On Pye, of note are his recordings of Elgar’s Enigma Variations and Cello Concerto (with Navarra), and rich interpretations of Dvořak’s last three symphonies, as well as many shorter pieces, several with operatic links. Towards the end of his life he also recorded one of the finest readings in the catalogue of the Symphony No. 2 by Sibelius, with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, for the Reader’s Digest organisation.

Barbirolli received no formal training in conducting. His musical response was instinctive and rooted in his experience as a string player. At the same time he was always extremely well prepared and a comparison of his conducting scores with his recorded performances demonstrates that he achieved all that he intended. His interpretations are notable for their spontaneity and lush orchestral tone. If at times he might linger over a particularly attractive phrase, the overall structure of a work remained intact. Barbirolli was not an orchestral disciplinarian: his relationship with his players was comradely. With his audiences he developed a natural bond that remains extraordinarily strong to this day: in the north of England his memory is recalled with an intense fervour. He was without question one of the finest British (and European) conductors of the twentieth century.

© Naxos Rights International Ltd. — David Patmore (A–Z of Conductors, Naxos 8.558087–90).