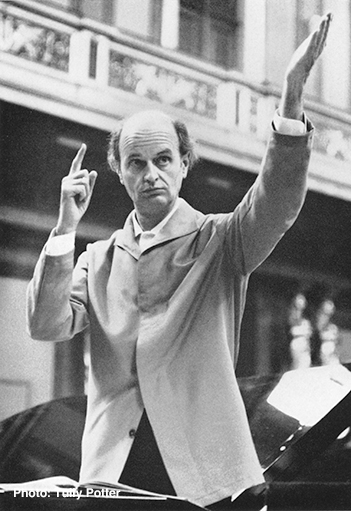

Ferenc Fricsay

The son of a military band conductor of great experience, and like him able to play a wide range of orchestral instruments, Ferenc Fricsay was a student for six years at the Budapest Academy of Music, where he studied violin and piano with Bartók and composition with Kodály. His first appointment came in 1933 as military bandmaster in the Hungarian town of Szeged, the economic and cultural capital of the south-eastern region of Hungary, adjacent to the Yugoslav and Romanian borders. In 1934 he became chief conductor of the Szeged Philharmonic Orchestra and went on to establish an opera department in the local theatre in 1939, making his debut as a conductor at the Budapest Opera in 1939. Fricsay stayed in Szeged until 1944 when he and his family went into hiding from the occupying German forces in Budapest, but following the defeat of National Socialism he conducted the first symphony concert in liberated Budapest in 1945, and in the same year was appointed chief conductor of the Budapest Opera and conductor of the Budapest Philharmonic Orchestra, of which Otto Klemperer was then a guest conductor. He made his debut with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra during 1946.

Fricsay’s international breakthrough came in 1947, when he substituted for Klemperer as conductor of the world première of Gottfried von Einem’s opera Dantons Tod at the Salzburg Festival. He was subsequently engaged as chief conductor of the Berlin RIAS (Radio In American Sector) Symphony Orchestra, the first of the six radio orchestras to be established by the occupying powers in Federal Germany, and held this post from 1949 to 1954 alongside that of chief conductor of the Berlin Stadtische Opera, a position which he retained until 1952. (The Berlin RIAS Orchestra was subsequently renamed firstly as the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra and then as the Deutsches Symphony Orchestra, while the opera company was renamed the Deutsche Oper, Berlin.) Fricsay made the RIAS Orchestra into one of the finest in West Germany. With the introduction of the long-playing record both he and the orchestra became mainstays of the new catalogue of Deutsche Grammophon Gesellschaft.

At the same time he was developing an international career, conducting the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra for the first time in 1948, returning to the Salzburg Festival to conduct Frank Martin’s Le Vin herbé in 1948 and Carl Orff’s Antigone in 1949, and conducting in England, Holland, Israel and South America. In 1950 he conducted the Glyndebourne Festival Opera’s production of Mozart’s Le nozze di Figaro at the Edinburgh Festival. Having appeared for the first time in America in 1953, leading the Boston Symphony Orchestra, the following year Fricsay took up the post of chief conductor of the Houston Symphony Orchestra in Texas, but stayed for only a short while, leaving following disagreements with the orchestra’s management. In 1956 he became chief conductor of the Bavarian State Opera, where he remained for two seasons before returning to his old post with the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra in 1959; he also acted as a musical adviser to the Deutsche Oper, and inaugurated the company’s new opera house in 1961, leading Don Giovanni. However by now he had been diagnosed as suffering from cancer and his final concerts were given with the London Philharmonic Orchestra at the Royal Festival Hall during December 1961.

Fricsay was unusual in that he insisted on and obtained great precision in his performances, yet combined this with considerable emotional force. In this respect his performances were quite different from those of Wilhelm Furtwängler, the other great Berlin conductor of the period when Fricsay was establishing his international conducting and recording career. These characteristics made him an ideal recording conductor, giving his recordings a power and freshness denied to many rival versions. He encouraged orchestral musicians to listen to each other, and to play as though in chamber music: consequently his performances possessed excellent internal balance, which also was a great advantage when it came to making records. Fricsay’s repertoire was extremely wide: he was equally at home in the opera house pit as on the concert hall podium. His accounts of operas by Mozart have well stood the test of time with their bustling vivacity, while his recording of Beethoven’s Fidelio has survived critical disdain to be recognised as a reading of real substance and dramatic power. The few recordings of live operatic performances conducted by him, such as a Rigoletto from Berlin in 1950, demonstrate a strong sense of musical theatre, and his recorded accounts of major choral works, such as Verdi’s Requiem, were also highly successful. He was a natural and authoritative interpreter of the music of his teachers Bartók and Kodály, leaving landmark recordings of the three Bartók piano concertos with his compatriot Géza Anda as soloist, and of the opera Duke Bluebeard’s Castle. He also led the first performance of Kodály’s Symphony in C at Lucerne in 1961.

But it is perhaps as an interpreter of the central late nineteenth-century repertoire, and especially the music of Tchaikovsky and Dvořák, that Fricsay will be best remembered. His readings of the three last Tchaikovsky symphonies, both in the studio and in the concert hall, possessed an intensity only rarely realised. In particular his landmark recording of Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 6 ‘Pathétique’ is powerful evidence of his ability to combine great instrumental precision with overwhelming emotional power. Fricsay’s musicianship was so keen and wide-ranging that anything to which he turned his hand was delivered with real understanding and style: his accompaniments to concerto recordings by Clara Haskil and Annie Fischer for instance remain models of their kind. To quote another highly distinguished musician, Yehudi Menuhin, ‘Fricsay was one of the world’s greatest conductors, certainly no conductor had greater talent.’

© Naxos Rights International Ltd. — David Patmore (A–Z of Conductors, Naxos 8.558087–90).