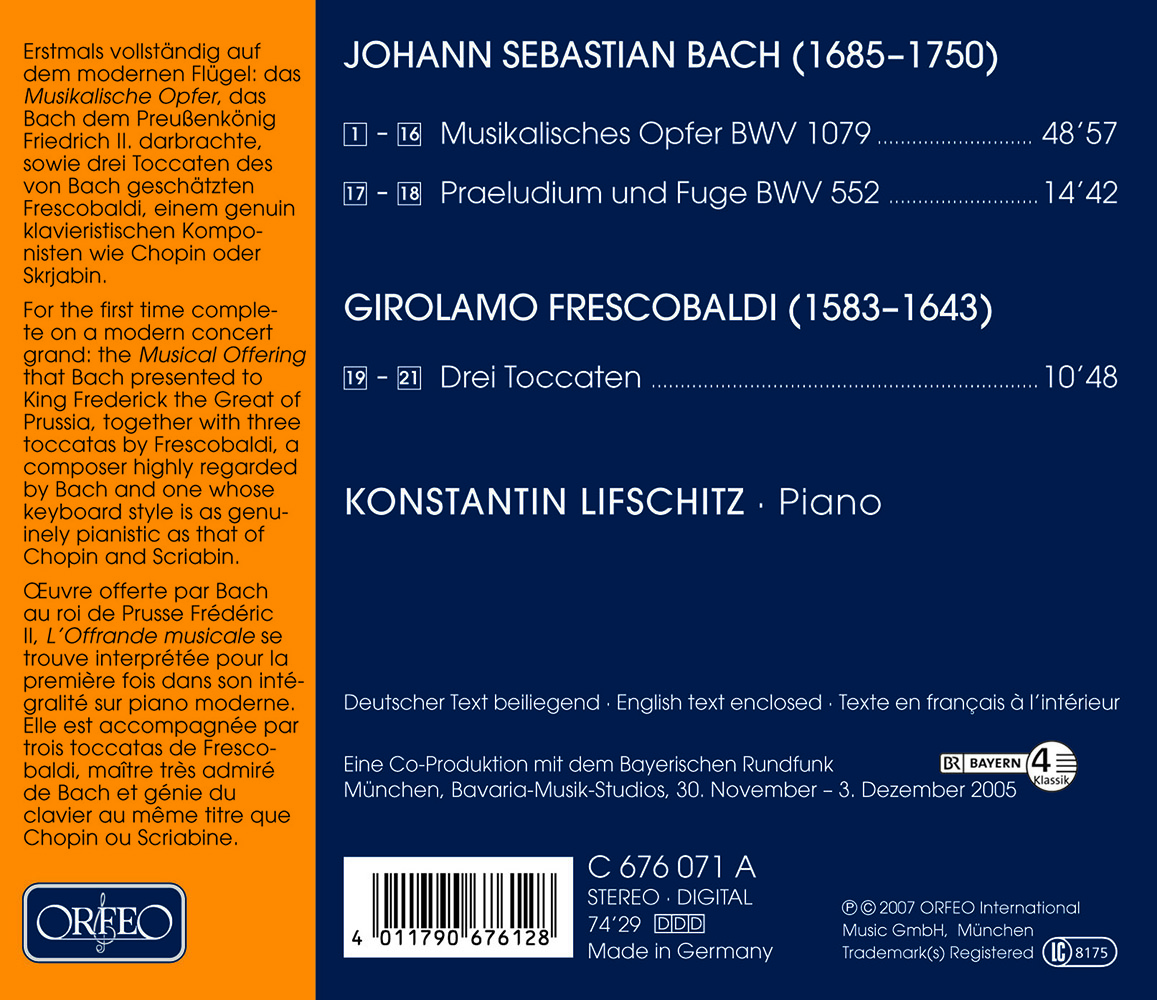

Musikalisches Opfer

It was only after six years’ preparatory work, during which time he consulted every available edition of the piece, that Konstantin Lifschitz

Konstantin Lifschitz

Foto: Christine Fenzlmade this spectacular recording of Bach‘s Musical Offering, the first to be made on a modern concert grand. The original famously includes a trio sonata scored for flute, violin and continuo, but Lifschitz was by no means deterred by this when arranging its movements for piano solo. Quite the opposite, in fact: it seems, rather, to have inspired him in terms of the range of sonorities produced by his playing and his sovereign ability to bring out the four-part writing of the original. Much the same is true of the six-part ricercar that Bach wrote in the wake of his visit to Potsdam in 1747 in response to a challenge from King Frederick the Great of Prussia, who invited him to improvise on a given theme. Fully aware that the „royal theme“ – the thema regium – was suited at best to a three-part fugue, Bach was able to submit this masterpiece only a few weeks later, describing the work as a „ricercar“, a term already old-fashioned by the 1740s. Konstantin Lifschitz describes any performance of the Musical Offering as tantamount to „crossing the Arctic Ocean barefoot“. In order to be able to perform it on his own, he plays the trio sonata and the canons as duets with himself, using a multi-track playback technique, much as Glenn Gould did when recording the final fugue in the overture to Die Meistersinger. In addition to the Musical Offering, Lifschitz also performs the Prelude and Fugue in E flat major BWV 552 from the third part of the Clavier-Übung – an attempt on the pianist‘s part to combine childhood memories of the cathedral organ in Riga with his own experiences as an organist, experiences that Lifschitz modestly describes as slight. The recital ends with three toccatas by the Vatican cathedral organist Girolamo Frescobaldi, who hailed from Ferrara and whom Bach held in high regard, a composer whose very specific pianism may be compared to that of Chopin and Scriabin. In the case of Bach, Lifschitz invites the listener to meditate on life, but these emotionally charged and atmospheric toccatas by Frescobaldi allow him, conversely, to add a highly personal postlude to his impressive new CD.